The Imperial Arms Industry had to struggle with some problems at the beginning of the war, which in the course of time would be solved, however, new and quite severe problems ensued.

The main problem that the Imperial Arms Industry saw itself confronted with at the beginning of the war was the fact that no proper preparations had been made for the event of war.

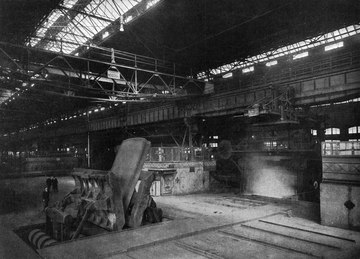

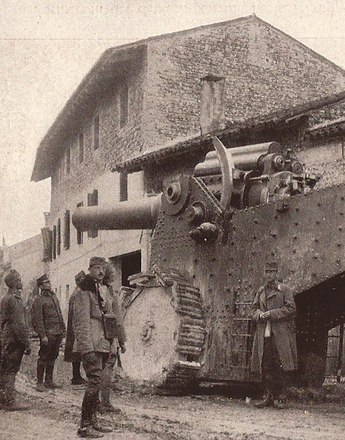

Thus there were only two production sites for metal working heavy industries – the Pils Škoda-Plant and the Wiener Artilleriearsenal – that met the requirements to produce the urgently needed war material. As the artillery just went through a process of modernisation though, these two factories had to be converted for the production of new types of weapons. Thus it was only in the course of 1915 that any noteworthy production numbers were achieved.

Concerning the other large arms factories of the Monarchy, like the Austrian Böhler Factory, the steel works in Witkowitz and Resicza as well as the gun factory in Györ, it was to take some time before they could produce the new types of weapons. The lack of any skilled workers was also problematic at the beginning of the war due to the mobilisation; this was only compensated for when exemptions from military service were gradually granted.

Nevertheless, from mid 1916 onwards the change from peace-time to war production had advanced in such a way that the Imperial Arms Industry could point to high or very high output figures. Yet this peak was only to last for a very short time, as from mid-1917 the production output already dropped dramatically.

What had happened in the course of this year? Only shortly after the successful change of the production infrastructures a new problem arose which was to hit the arms industries hard: the shortage of raw materials that started in the winter of 1916/17 which came to a head very quickly. In particular the trade embargo that impaired the supply of coal was to have a devastating effect on the arms industry. But there was also a shortage of lead, copper, iron ore and steel. But contrary to the coal shortage, the other shortages could be tackled to some extent by making economies, by using substitute materials or, as happened with copper, by using the copper roofs of churches and church bells. The lack of coal, however, was insoluble and had various consequences: for one thing, coal was an essential source material for the chemical industry and the production of the explosives that were needed in huge quantities. For another thing the smelting furnaces of the metal industries needed the coal for the extractive metallurgy. Also it provided the energy needed in the processing industries to fuel the machinery and production lines. Coal was also vital for transportation: on the one hand the steam locomotives that were fuelled by coal were to transport the war material to the front lines, on the other hand the industries that were based on the division of labour had to continuously be provided with 'raw materials and semi-finished goods'.

On top of the shortage of raw materials there was an increasing and dramatic shortage of food which demoralised the workers visibly. The resulting protests and strikes were the last straw that broke the camel's back: from spring 1918 onwards more and more factories had to discontinue their production completely. Thus the need for ammunition was only to be backed by the stocks from the army's high command – and those reserves would also have been depleted latest by spring 1919.

Ortner, M. Christian: Die k. u. k. Armee und ihr letzter Krieg, Wien 2013

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914-1918, Wien 2013

Ullmann, Hans-Peter: Kriegswirtschaft, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumreich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.), Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, 3. Auflage, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2009, 220-232

-

Chapters

- Explosive Discoveries. From Gunpowder to TNT

- From the Lorenz Gun of Königgrätz to the Ordnance Weapon M1895

- Artillery I.: Technical Innovation and late Modernisation

- Artillery II: The Creeping Barrage, Barrage and Curtain Fire

- The high rate of fire of the machine gun: concerning the Mitrailleuse, the Gatling Gun, the Maxim Gun and the Schwarzlose MG

- An Effective Addition: Hand Grenades and Mortars

- The Imperial Arms Industry