Artillery II: The Creeping Barrage, Barrage and Curtain Fire

Artillery and infantry were amongst the most important branches of the armed services in World War One, but they unfolded their full potential only in cooperation with each other. In this military union the artillery had to support the forward pressing infantry.

The military historian Christian Ortner writes that the artillery held the leading position among the branches of armed services in World War One: "There was no military action whatsoever that could be realised without the participation of the artillery."

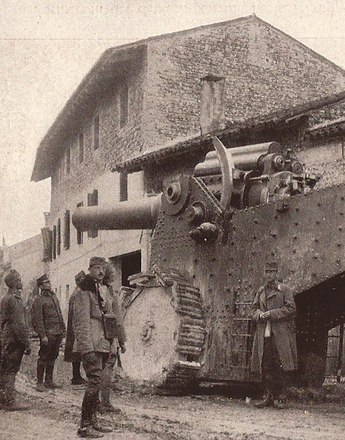

The artillery represented, as Ernst Jünger put it, 'the absolute reign of fire' with its enormous arsenal of various types of guns, mortars and howitzers. The artillery was the prototype of industrialised mass warfare – and of industrialised mass killing. No other armed services employed in World War One would cause more casualties than with artillery. The destructive powers of the guns – especially in its dense application – were enormous, as was the usage of ammunition. Thus in the 10th Isonzo Battle alone (from mid-May until the beginning of June 1917) 1.6 million projectiles were fired from more than 1,000 guns.

The artillery tasks were manifold: in mobile warfare it had to support the forward pressing infantry with its firepower. Yet there were repeated problems: the infantry was more mobile and quicker in open terrain than the artillery with its heavy guns that were difficult to transport, thus the former faced the enemy without the artillery having taken up its position. In that case the forces had to operate outside the sphere of activity of artillery fire.

The importance of artillery was even greater in positional warfare: here also it had to support or prepare the military operations of the infantry. Thus, for example, some areas were kept under constant fire with the so-called curtain fire, to make it more difficult for the enemy to march through and also to cut off the enemy's supply lines. With the tactics of the so-called creeping barrage it was necessary to support the infantry in such a way that the artillery's line of fire was moved forward by a certain distance in a synchronised time. This spasmodically advancing 'shell curtain' served as protection against enemy fire for the infantry that moved up closely along the line of fire and thus made it possible to gradually advance into the territory to be conquered. The barrage on the other hand served to prepare the enemy territory for the final charge by severe constant fire that often lasted for hours or even days. Next to the physical damage to the enemy it also served as psychological warfare. It was brought into operation as an 'attrition policy' which was to undermine the soldier's fighting morale and, according to Christian Ortner, it "[…] [broke] the perseverance of even the best of troops in the end." According to Michael Epkenhans the barrage was many times ranked among the most terrible experiences of soldiers and was often a trigger for war psychoses. One soldier described his experiences in his field post letter: "The rumble of gunfire is often so vivid that you don’t hear any individual shots, but a constant rolling that often lasts for hours on end. The people look downright dreadful when they've emerged from the trenches to return for their […] recuperation."

Epkenhans, Michael: Kriegswaffen - Strategie, Einsatz, Wirkung, in: Spilker, Rolf/Ulrich, Bernd (Hrsg.): Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914-1918, Osnabrück 1998, 69-83

Ortner, M. Christian: Die k. u. k. Armee und ihr letzter Krieg, Wien 2013

Ortner, M. Christian: Die österreichisch-ungarische Artillerie von 1867 bis 1918. Technik, Organisation, Kampfverfahren, Wien 2007

Quotes:

"There was no military action...": Ortner, M. Christian: Die österreichisch-ungarische Artillerie von 1867 bis 1918. Technik, Organisation, Kampfverfahren, Wien 2007, 551 (Translation)

"[…] [broke] the perseverance of...": Ortner, M. Christian: Die k. u. k. Armee und ihr letzter Krieg, Wien 2013, 155 (Translation)

„The rumble of gunfire is often...": Langhorst, Fr., quoted from: Epkenhans, Michael: Kriegswaffen - Strategie, Einsatz, Wirkung, in: Spilker, Rolf/Ulrich, Bernd (Hrsg.): Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914-1918, Osnabrück 1998, 72 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Explosive Discoveries. From Gunpowder to TNT

- From the Lorenz Gun of Königgrätz to the Ordnance Weapon M1895

- Artillery I.: Technical Innovation and late Modernisation

- Artillery II: The Creeping Barrage, Barrage and Curtain Fire

- The high rate of fire of the machine gun: concerning the Mitrailleuse, the Gatling Gun, the Maxim Gun and the Schwarzlose MG

- An Effective Addition: Hand Grenades and Mortars

- The Imperial Arms Industry