The Invention of Aerial Warfare and How War Propaganda Hyped up the Flying Aces as a Form of Motivation

It was only in the course of the war that specific types of aeroplane for specific forms of aerial warfare began to appear. What remained in people’s memory was above all the fighter planes and the aerial combat of the ‘flying aces’, who were also instrumentalized by wartime propaganda, which presented them as heroes.

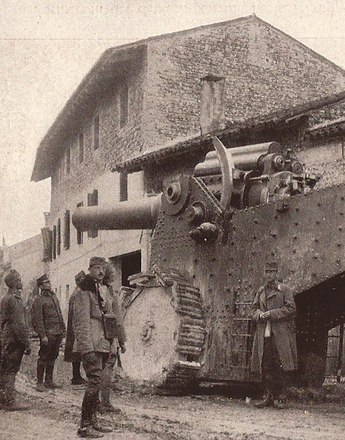

At the beginning of the First World War the belligerent powers did not yet have fixed, differentiated categories of aerial warfare and no exact ideas about how an air force could be used. The states involved had set up their first units for aerial warfare around the year 1910; formations for the use of balloons and airships had been in existence some time before. The first time that aeroplanes were used in combat was in the war between Italy and Turkey in North Africa in 1911. From 1914 on aircraft technology developed rapidly, as did tactical and strategic concepts and organisational structures for the air forces, with all areas being still at the stage where it was a case of ‘learning by doing’. This process basically led to the following uses for aeroplanes in war: Reconnaissance, Guiding artillery fire, Aerial combat between fighter planes, Support role for warplanes to assist ground troops and Bombing.

From the outset the military saw reconnaissance as the most plausible use for aircraft. The first large-scale battles on both the Western and the Eastern fronts showed the value of reliable aerial reconnaissance for conducting the war. Two-seater aeroplanes such as those used for reconnaissance were also suitable for guiding artillery fire, and in the course of the war they were equipped with radio sets for this purpose. Moreover, they could support ground troops by using onboard machine guns, hand grenades, small bombs and so on to attack the enemy. Initially it was especially Germany that used airships; in the course of the war large – even giant – aircraft with two or more engines were developed.

It is the dogfights between fighter pilots that have rooted themselves most firmly in the collective memory of the First World War. One of the first such pilots was the Frenchman Roland Garros, who made use of a machine gun mounted to fire forwards. The Germans took over this aircraft design for their Fokker E I, the first warplane to be equipped with reliable sychronization of the onboard machine gun with the propeller so that this would not be damaged when the pilot fired forwards. Such Fokker aircraft allowed the German air force to gain air supremacy on the Western front from August 1915 until well into 1916. Then a race in innovations and armaments set in, with the belligerent powers competing to produce the fighter plane which would be the most powerful in battle. The Germans and the Entente powers alternately got the upper hand. The aerial warfare of the fighter planes was instrumentalized for the purposes of propaganda. The so-called ‘flying aces’ were depicted as chivalrous heroes who fought for their side in man-to-man combat. Later this image was strengthened by specialist memoirs written on the subject.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Morrow Jr., John H.: The Great War in the Air. Military Aviation from 1909 to 1921, Washington/London 1993

Schmidt, Wolfgang: Luftkrieg, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard et al. (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2003, 687-689

-

Chapters

- Powered Flight as a New Technology

- The Invention of Aerial Warfare and How War Propaganda Hyped up the Flying Aces as a Form of Motivation

- The Origins of the Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Aviation Corps

- The Beginnings of Aircraft Manufacture in Austria

- The Situation of the Austro-Hungarian Aviation Corps in the Years 1914-15

- The Procurement Campaign of 1915-16 and the ‘Knoller Programme’

- The Most Important Aircraft Types of the Austro-Hungarian Aviation Corps and Their Wartime Service