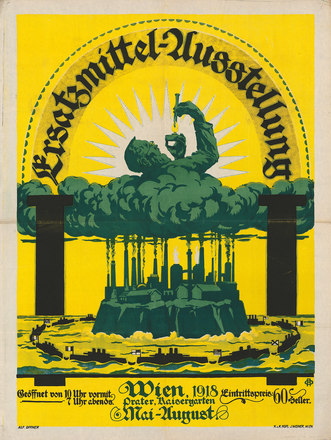

The Prater offered entertainment, but it was also used for military propaganda. In the last months of the war an exhibition was organised there on surrogates. Although the intention was the opposite, it showed how difficult it had become to manage on a day-to-day basis.

The Prater had always been a venue for major exhibitions. This tradition was also exploited for military and patriotic purposes. In 1916 there was a major war exhibition, showing the military materiel of the Central Powers, equipment acquired from the enemy, and art, literature and photographic exhibits. Visitors could play “war games” in a model trench system.

An exhibition on surrogates was staged in May and June 1918. It showed the degree to which these substances were being used but also the desperate efforts to improve their acceptance. The foreword to the catalogue stated: “In some cases unknown and used reluctantly, suspiciously and hence unsuccessfully, these surrogates have not yet been accorded the place in the wartime economy that they deserve.”

The exhibition concentrated on commonplace wartime applications – food and household tasks, shoes, paper textiles and substitute leather. The oil and fat section showed ersatz fats such as war soups made from de-oiled seeds, fat obtained from sheep’s wool, fat-collection devices and substitute soap or “Schwindelseife”, referring to the inferior quality of household soap.

The population had become accustomed to supplementing their diet with mushrooms and berries, wild vegetables and lichen. The Department of Food provided samples and figures. In 1917, a good 1,260 tons of ersatz tealeaves, chestnuts and acorns were purchased by the 756 collection points. The Austrian Pharmacy Society’s Research Institute for Food and Semi-Luxury Goods showed ersatz meat, eggs, flour, cocoa, coffee, tea, tobacco and edible oil. Cooking boxes were recommended for fuel economy when preparing food. Animals were also given inferior feed made from sugar waste and straw. Several Catholic woman’s organisations presented campaigns such as the “Spinnrad im Weltkrieg” for self-sufficiency, a “sock clinic” with advice for protecting paper clothes, and tips for making children’s clothes from silk waste and dog hair and dolls from waste.

Shoes from Mitterndorf refugee camp had soles made of wood, regenerated rubber or waterproof felt. Many surrogates had promising names like Futurit, Gummoid or Gummon. The synthetic resin Abalak could be used, so it was claimed, to make rosin for lacquers and varnishes, while Juvelith replaced amber, ivory and coral. Around one hundred companies advertised their products in the catalogue.

Translation: Nick Somers

Katalog der Ersatzmittel-Ausstellung Wien 1918, hg. von der Ausstellungskommission, Wien 1918

Sommer, Monika: Zur Kriegsausstellung 1916 im Wiener Prater „als mächtige Antwort der Monarchie an das feindliche Ausland“, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 502–513

-

Chapters

- Chicory, peat & Textilit: surrogates before the war

- The age of iron

- Bells for bullets: metal collection

- Fragile clothing: textiles and paper fabrics

- Well shod? Tanning agents and leather

- Rubber goods: elastic and essential

- From far and near: resins and resin products

- The 1918 surrogate exhibition in the Prater