Voyaging and travelling: tourism and tourism films

In the nineteenth century people’s experience of the world had expanded, and the world itself was larger and also more accessible, thanks not only to the faster means of transport but also to the cinema.

The cinema offered new forms of perception, as country landscapes and towns were filmed in panoramic sweeps from above. The travel experience was further enhanced by ‘phantom rides’. Moving vehicles – trains, buses, automobiles, ships – became mobile film platforms offering a new way of capturing the feeling of the countryside. Film-makers gave the public an opportunity to travel without leaving their seats. ‘In a few minutes,’ they claimed, it is possible to rush through ‘countless landscapes’, ‘be present at events that would not otherwise be seen’ and at the same time ‘obtain enriching new information’ (Österreichischer Komet, no. 5, 1908).

The first highpoint of cinematography also coincided with the start of mass tourism. The excursion to the country, initially on foot or in a rented carriage, then by train and later by bicycle or even automobile, was one of the great achievements of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The urban intelligentsia discovered the Alps. Wealthy summer vacationers moved with their entourage to the Vienna Woods, Südbahn region, Salzkammergut, Adriatic, Dalmatian coast, South Tyrol, Wildbad Gastein, the southern Styrian spas and the Carinthian lakes.

The publicity potential of travel pictures was soon recognized and exploited. It was foreign companies who first presented Austro-Hungarian landscapes and attractions, however. In 1907 the British company Charles Urban Trading Co. produced the film Beauties of Tyrol with the support of the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Railways. Eventually, the state authorities also began to show an increasing interest in cinematographic tourism propaganda. In 1911 the Austrian Ministry of Labour sent two senior tourism officials on a publicity tour. They took the necessary films with them and gave talks in all of the major cities of Europe. Among the films were pictures of Tyrol, Salzburg and eastern Styria. Other cinematographic landscape pictures from Austria were made available free of charge to major German film distributors.

The series Austria in Moving Pictures produced by the Vienna branch of the Éclair company in 1913 was an advertisement for the country that was distributed worldwide. Two films in the series attracted particular attention. They showed burlesque episodes against the background of interesting landscapes. The humorous and dramatic action was the focus of attention, with the ‘natural beauty of Austria’ provided a picturesque setting. The film Eva’s Rose Garden (A 1913) had a young American woman visiting south Tyrol. Accompanied by a dashing mountain guide, she negotiated dangerous rock faces, learnt about the people and their customs, admired the national costumes of Gröden [Val Gardena] and local woodcarvings. In the end it was not only the magnificence of the Dolomites that won her heart but also her gallant companion. In the film Between Two Fires (A 1913) the bon vivant Gottlieb is ordered by his doctor to take a cure in Semmering. While out walking he meets a brunette and a blonde lady and courts both of them. The young women write to their husbands about Gottlieb’s advances. The two men duly arrive and the womanizer is forced to make his escape. During this humoresque, the viewer is offered views of practically the entire Semmering region. ‘The cleverly chosen musical accompaniment,’ reported Filmkunst (no. 11, 1914), enhanced ‘the suggestive force of the humorous scenes.’

Among the main producers of Austrian travelogues before the outbreak of the First World War until 1912 was the team Kolm-Veltée-Fleck. Thereafter the scene was dominated by Sascha Kolowrat. Only a few of these pictures have survived. The film Bozen and the Climatic Spa Gries (A 1913) offered not only impressions of the region for tourists but also an atmospheric phantom ride with the Guntschna [Guncina] cable railway.

Translation: Nick Somers

Deeken, Annette: Geschichte und Ästhetik des Reisefilms, in: Jung, Uli/Loiperdinger, Martin (Hrsg.): Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland, Band 1, Kaiserreich 1895–1918, Stuttgart 2005, 299-323

Eigner, Peter/Helige, Andrea (Hrsg.): Österreichische Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Wien/München 1999

-

Chapters

- Cinematic fascination: the machine in war propaganda

- Mobility in film: conquering new spaces

- The thrill of speed in film: heroes of the road and air

- Voyaging and travelling: tourism and tourism films

- Capturing the unusual: the Vienna Prater

- Movement in films – sport, gymnastics and physical culture

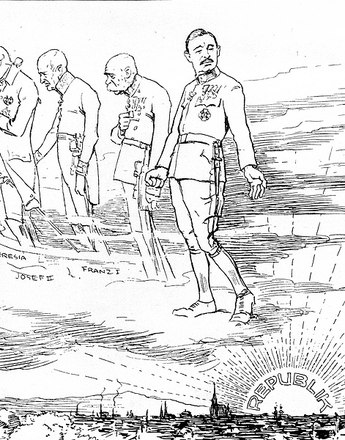

- Power and the public: political movements in historical films