A National Hero Forever

Eugene’s last days and the lion of the Belvedere... the King of France, whom he had so often defeated, gave him an African lion... at last there were three days when the lion saw his master no more, refused all food and paced up and down restlessly inside his cage... at around three o’clock in the morning, he let out such a roar that his keeper ran out into the menagerie to see what had happened. There he saw lights in all of the chambers of the palace and heard the death knell in the chapel. Thus he knew that his Master, the great Prince Eugene, had died at this hour. (Hofmannsthal, Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter [Prince Eugene the Noble Knight])

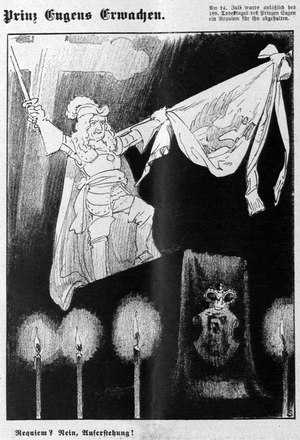

Historical personages have served since time immemorial as figures onto which (usually) idealized portrayals of nations and peoples can be projected. During wartime, it is, naturally, victorious historical military leaders who are the figures of choice to be instrumentalized for propaganda purposes. In Austria, this was Prince Eugene of Savoy, who was celebrated in essays, poems and in children’s literature during the First World War.

The fact that Eugene came from France, the enemy nation, and that his most significant military victory in Austrian historical memory had been against the current military ally, the Turks, made no dent in the cult that surrounded him. Hugo von Hofmannsthal, in particular, showed himself to be deeply impressed by the man who was probably the best-known commander in Austrian history. In the 1914 Christmas supplement of leading Austrian daily the Neue Freie Presse, he paid tribute to the General’s virtues in Worte zum Gedächtnis des Prinzen Eugen [Words in Remembrance of Prince Eugene], to whom he attributed the gift of providing an inexhaustible source of hope in this time: ‘But one man was able to do more than can be said, and again and again, at appropriate intervals, Providence summons the man from whom the greatest feats are demanded and who can face up to the greatest challenges.’

Hofmannsthal complained that there was too little children’s literature available about great historical figures. Since ‘young people, and others, cannot learn to love the Fatherland without legends’, in 1915, he published his illustrated children’s book, Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter: Sein Leben in Bildern [Prince Eugene the Noble Knight: His Life in Pictures]. Based on historical sources, in the book he describes Louis XIV, who fails to recognize Eugene’s talent and expels him from the court. In a stroke of good historical fortune, the Austrian emperor Leopold acts with greater foresight, and takes Prince Eugene, a paragon of self-discipline, into his employ. The alliance of Austria and Germany is also presented in a positive light, as Prince Eugene recognizes at an early stage that the origin of the German malaise lies in the fragmentation of the German Länder. According to Hofmannsthal, credit for Austria’s salvation lies primarily in Eugene’s bravery and outstanding military achievements. His victory against the Turks had ‘broken their grip on power forever, just as has happened in our time to the half-Asian Great Power, the Russians, thanks to God’s assistance, and, we hope, for all time’. With these words, he makes an unambiguous judgement, expressing his view of the First World War and the central role of the alliance of the German and Austro-Hungarian empires.

At the end of the book, Hofmannsthal introduces the famous song about Prince Eugene with the words: ‘Prince Eugene’s soul is always there, wherever our soldiers do battle and are victorious.’ Here, Eugene’s actions are overtly posited as a model and a mission for the soldiers of the First World War.

Translation: Aimee Linekar

Hiebler, Heinz: Hugo von Hofmannsthal und die Medienkultur der Moderne, Würzburg 2003

Hofmannsthal, Hugo v.: Worte zum Gedächtnis des Prinzen Eugen, in: Neue Freie Presse vom 25.12.1914, 35-40. Unter: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=nfp&datum=19141225&zoom=33 (19.06.2014)

Hofmannsthal, Hugo v.: Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter, sein Leben in Bildern. Erzählt von Hugo von Hofmannsthal. 12 Original-Lithographien von Franz Wacik, Wien 1915

Sauermann, Eberhard: Schreiben im Namen des Vaterlands: Hofmannsthal, in: ders.: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg [Literaturgeschichte in Studien und Quellen 4], Wien/Köln/Weimar 2000, 38-44

Zimmermann, Christian v.: Biographische Anthropologie. Menschenbilder in lebensgeschichtlicher Darstellung (1830-1940), Berlin 2006

Quotes:

„Eugene’s last days ...": Hofmannsthal, Hugo v.: Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter, sein Leben in Bildern. Erzählt von Hugo von Hofmannsthal. 12 Original-Lithographien von Franz Wacik, Wien 1915 (Translation)

„But one man was able ...", „young people, and others ...": Hofmannsthal, Hugo v.: Worte zum Gedächtnis des Prinzen Eugen, in: Neue Freie Presse vom 25.12.1914, 35-40. Unter: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=nfp&datum=19141225&zoom=33 (19.06.2014) (Translation)

„broken their grip on power ...": Hofmannsthal, Hugo v.: Prosa, Bd. 3, Frankfurt am Main 1952, 291-319, hier 292, zitiert nach: Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg [Literaturgeschichte in Studien und Quellen 4], Wien/Köln/Weimar 2000, hier: 44 (Translation)