Artillery I.: Technical Innovation and late Modernisation

In 1900 it became more than apparent that the guns of the Imperial Artillery were by and large outdated compared to those of the other Great Powers. An extensive process of modernisation was to balance out that deficiency. Yet the projected new gun models could not be brought to readiness for start of production before the beginning of the war in 1914.

Since the mid 19th century there had been important innovations in artillery guns. The British industrialist and inventor William G. Armstrong (1810-1900) first constructed a field gun with a rifled barrel which substantially improved the range and accuracy of the projectiles. This type of field gun was highly innovative and thus introduced to many different armies.

The next important innovation came from France at the end of the 19th century: the French developed a gun with a recoil brake, which absorbed most of the recoil energy engendered when firing a gun. Thereby the gun was stabilised and did not have to be newly adjusted after every shot. In this way a higher rate of fire and accuracy was achieved with a simultaneously lower work input. By virtue of these crucial advantages the French canon de 75 modèle 1897 was considered a revolutionary innovation in the area of artillery guns. Many states imported this gun or produced it under special licence and it remained in use in the French army right up to World War Two.

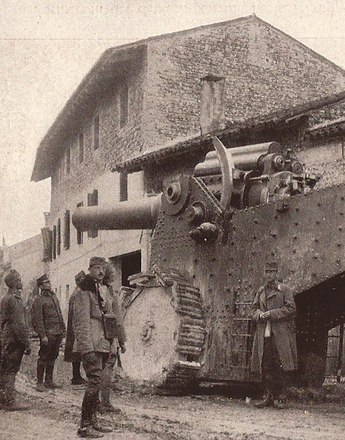

The Imperial Army was in a transition period in 1914: it became already apparent in 1900 that the 'machinery park' had to be modernised. The technically outdated guns had fallen far behind the standards of the other Great Powers when it came to range, rate of fire and effectiveness. However, the refitting to more modern guns had by no means been completed when war began. Therefore the artillery units of the Imperial Army had only a small number of modern equipment, mainly old rifles and some prototypes that were still in the developing phase at its disposal. The industrial large scale production of the urgently needed new guns did not quite want to get started. Another problem was the fact that the Habsburg industries were not sufficiently prepared for the sudden requirements. The armament production could only get really started in 1915 but it was not until 1916 that the required numbers could be produced. But this procrastination also had one advantage: the earlier experiences in battle had an influence on the new constructions. This lead to some of the guns developed during the war – like the 7.5 cm mountain gun M.15, the 10.4 cm gun M.15 or the field howitzer M.14 – ranking among some of the best guns of their time. On the other hand it came to considerable delays due to long term trial phases, as happened with the field gun M.17 and M.18. Ultimately the Habsburg industries managed not only to replace old artillery material with new modern types, but also to raise the number of guns significantly until 1918.

Ortner, M. Christian: Die k. u. k. Armee und ihr letzter Krieg, Wien 2013

Ortner, M. Christian: Die österreichisch-ungarische Artillerie von 1867 bis 1918. Technik, Organisation und Kampfverfahren, Wien 2007

-

Chapters

- Explosive Discoveries. From Gunpowder to TNT

- From the Lorenz Gun of Königgrätz to the Ordnance Weapon M1895

- Artillery I.: Technical Innovation and late Modernisation

- Artillery II: The Creeping Barrage, Barrage and Curtain Fire

- The high rate of fire of the machine gun: concerning the Mitrailleuse, the Gatling Gun, the Maxim Gun and the Schwarzlose MG

- An Effective Addition: Hand Grenades and Mortars

- The Imperial Arms Industry